In 2017, Sri Lanka’s country score in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) declined to 4.09 out of 7. This is the lowest score Sri Lanka has received since 2010. Sri Lanka’s ranking in 2017 also declined to 85th out of 137. This is the lowest that Sri Lanka has been ranked since being included in the GCI in 2001.

The GCI score is calculated using two types of indicators: objective (or measurable) indicators and subjective (or sentiment) indicators. This Insight is based on work done by Verité Research to disaggregate the GCI score into these two types of indicators. It finds that Sri Lanka has been improving on the objective indicators and declining on the sentiment indicators. The decline in Sri Lanka’s overall score and ranking is due to the steep decline on the sentiment indicators – which overshadowed the improvements on the objective indicators.

Global Competitiveness Index

The GCI is a composite index that ranks the economic competitiveness of countries based on “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country”. The competitiveness ranking is widely used as a measure of a country’s relative attractiveness and potential for investment and growth. The index is collated and published by the World Economic Forum.

The GCI index calculates an overall competitiveness score between one and seven (with seven being the highest) for each country and ranks them accordingly. The latest scores and rankings of the GCI were published in the Global Competitiveness Report 2017/18, which was released end-September 2017.

Sri Lanka recorded its highest score and rank in 2011 with a score of 4.3 and a rank of 52. Thereafter, Sri Lanka’s competitiveness score has been declining, except for 2015, where it spiked up again to 4.22. For a summary of Sri Lanka’s performance in the GCI between 2011 and 2017, refer Exhibit 1.

Ups and downs of Sri Lanka’s competitiveness score

In this period, Sri Lanka has experienced two phases of decline (2011-2014 and 2015-2017) and one period of incline (2014-2015) in its competitiveness score. These three phases will be explained below.

Decline from 2011-2014: This decline can be explained in part by the changes in how the index was scored for Sri Lanka. In this period, Sri Lanka’s economy transitioned from low-income to middle-income status. In the terminology of the GCI index, it transitioned from a ‘factor-driven economy’ to an ‘efficiency-driven economy’. The GCI scores these types of economies differently, placing different weights on the indicators. This is because the indicators that matter more for competitiveness change as economies transition.

The result of this change was that certain indicators for which Sri Lanka previously scored high were given less weight and vice-versa. These changes were given effect from 2012 to 2014 and can significantly account for the drop in Sri Lanka’s GCI score after 2011. Verité Research’s insight titled ‘Sri Lanka’s Competitiveness is Stagnating: Efficiency is the Issue’, published on October 10, 2015, further explains the reasons for this decline.

2015 rise and 2015-2017 decline: Sri Lanka’s GCI score rose sharply in 2015 and has been declining steeply since then. However, the weightage given to each indicator has remained the same after 2014. This begs the question: what explains the 2015 increase and the subsequent decrease in Sri Lanka’s score? The next section unravels this puzzle. The answer, in short, is that it is the sentiment indicators, as opposed to the objective indicators, that have driven the change in the competitiveness score after 2014.

Two types of GCI indicators

The GCI is constructed based on a set of 114 indicators. Of these, 80 are sentiment indicators and 34 are objective indicators.

Sentiment indicators: Examples of sentiment indicators used include wastefulness of government spending, efficiency of legal framework, judicial independence, quality of overall infrastructure, quality of roads and ethical behaviour of firms.

The sentiment indicators are scored using the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey, which is administered every year from February to June. The survey captures the opinions of business leaders and is administered through the forum’s network of partner organisations.

Objective indicators: Examples of objective indicators used include exports to the GDP ratio, country credit rating, phone/Internet subscriptions, education enrolment and patent applications.

The objective indicators are scored using available statistical data from different sources, such as the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, UNESCO and International Financial Corporation.

Sri Lanka’s score in 2017

In 2017, of the 80 sentiment indicators, Sri Lanka’s score increased for only six, declined for 67 and remained the same for seven. To state this in another way, Sri Lanka’s score decreased for over 80 percent of the indicators and increased for less than 10 percent of the indicators.

Meanwhile, of the 34 objective indicators, Sri Lanka’s score increased for 21, declined for seven and remained the same for six indicators. To state this in another way, Sri Lanka’s score decreased for only around 20 percent of the indicators, while it increased for over 60 percent of the indicators.

Decline in total score driven by decline in sentiment scores

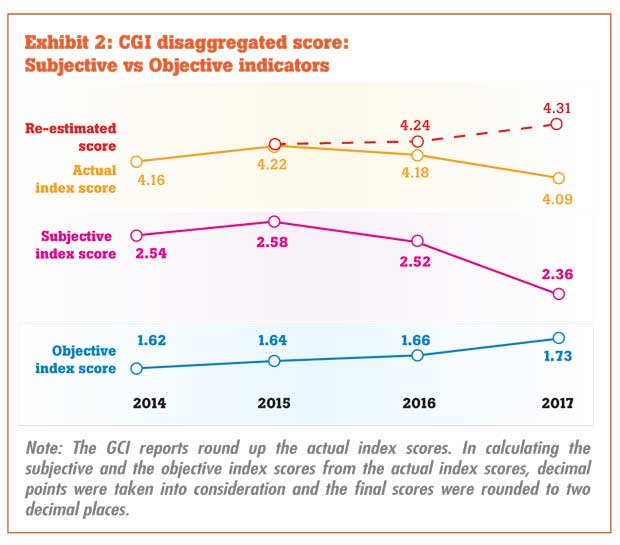

Verité Research reverse engineered the calculation of the GCI index and separated the total score of the index into two components: the sentiment score and objective score. The results are displayed in Exhibit 2.

Explaining findings

2014-2015: Sri Lanka’s competitiveness score improved between 2014 and 2015. This increase was driven by an increase in the subjective score, which rose by 0.04 (or 1.57 percent) and an increase in the objective score, which rose by 0.02 (or 1.23 percent).

One factor that could account for these increases is the 2015 election. That is, on the back of an election that saw the political power change hands, there was a general sense of positive optimism that boosted the sentiment indicators.

2015-2017: In the 2015-2017 period, the scores for the sentiment indicators began to decrease steadily: they decreased by 0.06 from 2015-2016 and took a further nosedive of 0.16 from 2016-2017, falling below even the 2014 level; overall, the sentiment scores decreased by 8.53 percent between 2015 and 2017. Conversely, the scores for the objective indicators continued to increase in the 2015-2017 period: they increased by 0.02 from 2015-2016 and then increased significantly by 0.07 from 2016-2017. Overall, the objective scores increased by 5.49 percent between 2015 and 2017.

One factor that could account for these changes is that positive sentiment steadily diminished under the new government, despite the improvements that were being made on an objective scale.

Projection of 2017 scores with 2015 sentiment: It is possible to project Sri Lanka’s competitiveness score and ranking to what it would have been if the positive sentiment gained in 2015 had been maintained alongside the improvements in objective indicators that were actually achieved. The re-estimated scores are shown in red in Exhibit 2.

This re-estimated score shows that Sri Lanka’s competitiveness would have been at an all-time high (at 4.31) instead of an all-time low (at 4.09); Sri Lanka’s competiveness rank in the world would have been 62 instead of 85. The re-estimation reveals the extent to which the downward turn in sentiment has overshadowed improvements in objective indicators since 2015.

In economics as in politics, sentiment – whether positive or negative – cannot be dismissed as mere sentiment, even when it is at odds with objective reality. This is because people tend to act based on their sentiment, both in terms of political decisions (i.e., voting) and economic decisions (i.e., consumption or investment). These decisions then shape real outcomes. Therefore, whatever the prevailing sentiment may be, it can be self-fuelling and draw reality in its direction.

Taken from Dailymirror.lk