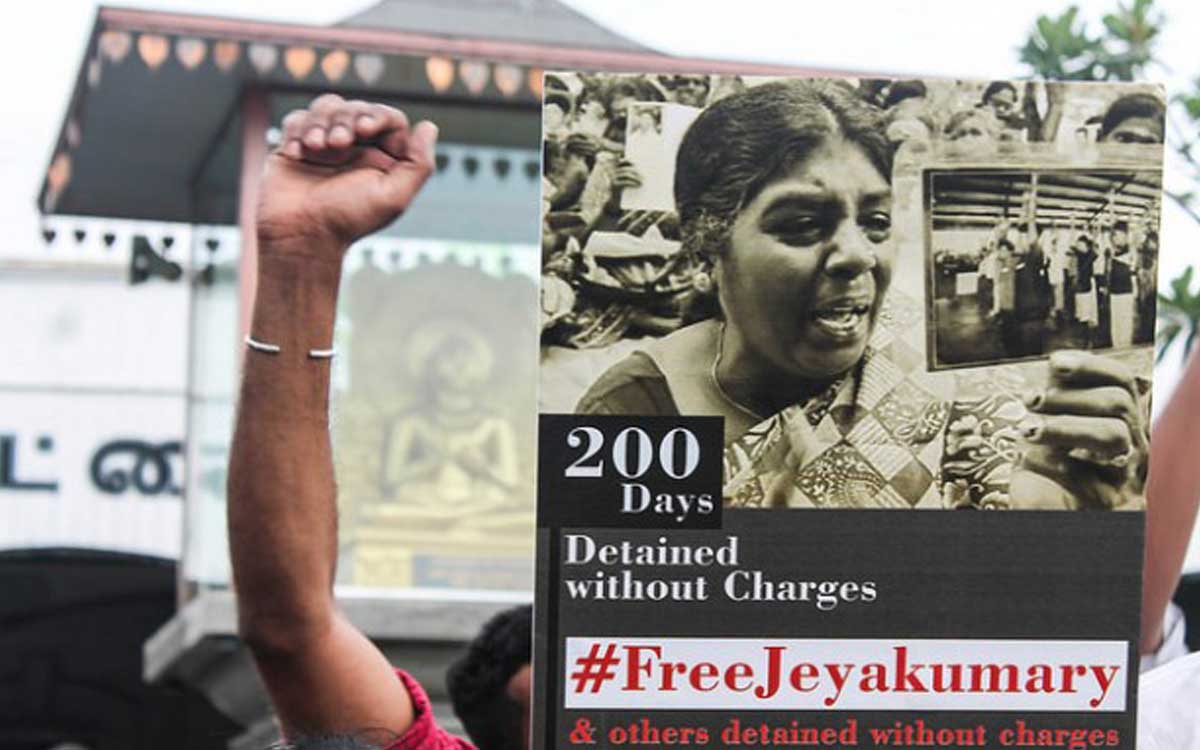

Jeyakumari Balendran, an activist campaigning for the whereabouts of missing persons in Sri Lanka, was detained by officers of the Terrorist Investigation Division (TID) in March 2014. Photo: Vikalpa | Groundviews | Maatram | CPA / Flickr

Nearly a decade after the end of the civil war, Sri Lanka’s draconian anti-terrorism laws – which give sweeping powers to policing authorities and allow arbitrary detention of suspects – are still in the books. A government pledge to repeal and replace the existing Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) has seen slow progress. Last year, the cabinet approved a pre-bill draft for the proposed Counter Terrorism Act (CTA), which came under criticism from legal experts and the civil society for retaining objectionable aspects of older counterterrorism laws. The bill has yet to be tabled in the Parliament.

In this interview, human-rights lawyer and researcher Gehan Gunatilleke talks to us about the problems with Sri Lanka’s proposed anti-terrorism laws, how it falls short of the government’s own commitments, and argues that any special legislation targeting ‘terrorism’ is fundamentally flawed and unnecessary.

Himal Southasian: Could you briefly describe the proposed Counter Terrorism Act (CTA), the current state of the bill and how is it different from the Prevention of Terrorism Act (1978) it was intended to replace?

Gehan Gunatilleke: The cabinet approved ‘Policy and Legal Framework relating to the Proposed Counter Terrorism Act of Sri Lanka’ in April 2017. At that stage, there was no bill as such, as the Legal Draftsman’s Department had not converted the document into a bill. The document has since been converted into a bill, but it is not in the public domain. So I can only comment on the cabinet-approved document of 2017.

There were three major problems with the 2017 document. First, it contained an extremely broad definition for the offence of ‘terrorism’. The offence included within its scope acts committed with the so-called purpose of causing harm to ‘unity’. Unity is an extremely vague term that can be interpreted in many ways. For example, criticism of governmental leaders, or the clergy, may easily be framed as harming unity. Second, the 2017 document made confessions to police officers admissible as evidence against the accused. A similar scheme is present in the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and has been heavily criticised as potentially incentivising coercive interrogations and torture. Third, it denies prompt access to legal counsel of the suspect’s choice, which can undermine the rights of suspects to a fair trial – particularly given the fact that their statements could be used as evidence against them.

I understand that some of these issues may have been addressed in the latest version of the counterterrorism bill. But since the government has not disclosed the bill to the public, I am not in a position to confirm that. It does, however, raise a more systemic problem in Sri Lanka about the legislative drafting process. Too often, the process is shrouded in secrecy, thereby denying the public and legal scholars an opportunity to scrutinise legislation. Also, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, which has a statutory mandate to assess draft legislation with human rights implications, needs to be more regularly and systematically consulted on drafts.

HSA: The current government committed to make the draft of the law conform with “contemporary international best practice”. How accurate is that claim and what are these best practices?

GG: I think some government actors are largely committed to aligning the new law with ‘contemporary international best practices’. However, I think that there is some disagreement among the various actors within the government on that matter. The national security establishment including the TID and representatives of the armed forces will be hesitant about reducing the powers of the state to combat anti-state elements. Meanwhile, other sectors in government, including the foreign affairs sector and the justice sector, will be keen to ensure the new law meets international and domestic expectations.

Current international best practices usually include short administrative detention periods, guaranteed access to legal counsel, and reasonably clear definitions for offences. Regardless of how compliant the law is with international best practices, we should be asking whether these so-called international best practices are worth emulating in the first place. I think the entire international regime itself is fundamentally flawed from the standpoint of legal certainty, which is a fundamental pillar of any society based on the rule of law.

Legal certainty is simple: it means a citizen should be able to predict how the law applies to him or her, and the law should be clear and predictable. Now if some executive authority, such as the police, gets to arbitrarily decide which procedure would apply to a suspect, legal certainty breaks down. So regardless of whether the new law is compliant with international best practices on counterterrorism, it will be deeply problematic in terms of legal certainty.

HSA: The need for legislations specifically targeting ‘terrorism’ seems to be taken for granted by governments and policy makers around the world. Should we be skeptical of that assumption?

GG: Absolutely. Special legislations, such as the proposed bill, stipulate a separate procedural regime applicable to ‘terrorism’ cases. Why is this a problem? Think of two procedures for prosecution – A and B. Procedure A guarantees to suspects all the basic rights, such as the freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, and all fair-trial rights including freedom from self-incrimination. Procedure B, meanwhile, permits suspects to be detained for longer periods of time and restricts fair trial rights, such as the presumption of innocence. If Procedure A applies to all offences (Offence X) in general and Procedure B applies to just some special offences (Offence Y), we run into a serious problem from the perspective of legal certainty. This is because the choice of which procedure to apply to a suspect will depend on which offence he is ‘suspected’ of having committed. And that decision is then left to an executive authority such as the police.

For example, let’s say theft committed ordinarily (Offence X) would attract Procedure A, whereas theft committed with the intention to damage the territorial integrity of the country (Offence Y) would attract Procedure B. But that so-called intention is a matter of evidence, which has not been proved at the time of selecting which procedure to apply. One could only establish such specific intention after a trial. This means that the police officer gets to decide arbitrarily which procedure to apply. And in some cases, the accused is eventually acquitted. For example, a Tamil woman who was detained for fifteen years under the PTA was eventually acquitted. The person underwent grave violations of human rights – long term detention and denial of fair trial rights – because a special procedural regime was applied to her by law enforcement authorities under the PTA (as opposed to ordinary law).

It is far better to have one common procedural regime that applies to all offences. One could then conceive of special offences that have additional elements such as the intention to intimidate a population, but such offences can only be proved during a trial in a court of law.

HSA: Won’t such common procedural regime harm the state’s ability to investigate ‘terrorism’ offences?

GG: I doubt that. Take for example, the investigations into the attempt to assassinate Tamil National Alliance MP M A Sumanthiran. The PTA was not used to arrest, detain or investigate the suspects. However, at no point have law enforcement authorities suggested that the ordinary law was inadequate to conduct their work. The Bail Act of 1997 provides ample space for a judge to deny bail to a suspect on the basis that he might commit another offence or attempt escape. Thus, any serious threat a suspect might pose to national security can be assessed by a competent judge under Sri Lanka’s ordinary criminal law. We do not need special procedural regimes that grant discretionary power to executive authorities.

I think a clearly defined offence – whatever you want to call it – can be included in criminal law, provided the procedural regime applicable to those suspected of the offence is the same as what is applicable in general. So, if a state wants to draft a law that establishes the offence of ‘terrorism’, it can do so, provided that the elements of the offence are crystal clear. For example, a person who commits murder with the additional intention of intimidating a population could be convicted of a special offence (call it ‘terrorism’) after evidence of such intention is established during a trial. But a person suspected of the offence (‘terrorist suspect’) should not be subjected to a separate procedural regime merely because of this suspicion.

HSA: How have such counterterrorism laws been abused in Sri Lanka?

GG: I think punishing opponents of the state has been the primary arena of abuse. Journalists such as J S Tissainayagam have been arrested, detained, prosecuted and convicted under the PTA. Politicians such as Asath Salley have been arrested under the PTA for criticising governmental inaction on ethno-religious violence. Former army chief Sarath Fonseka was prosecuted for causing ‘public alarm’ under provisions of the 2005 Emergency Regulations (similar to the provisions of the PTA) in the White Flag Case following his bid for the presidency in 2010.

HSA: Could you tell us something about the history of special laws on terrorism, and its philosophical underpinnings?

GG: The historical and philosophical underpinnings of most if not all counterterrorism laws is the protection of the state from anti-state actors. It is the preservation of power structures that motivates these laws – not necessarily the protection of civilians. I think we have to confront this reality head on. Take the preamble of the current PTA for example. It betrays the intention of the law: “Whereas public order in Sri Lanka continues to be endangered by elements or groups of persons or associations that advocate the use of force or the commission of crime as a means of, or as an aid in, accomplishing governmental change within Sri Lanka (emphasis mine).”

HSA: What has been the record of bodies like the Terrorist Investigation Division (TID) of the Sri Lanka Police – which has a history of indulging in arbitrary, extrajudicial activities – since the end of the Rajapakse rule? Has the body seen change since then or are they still abusing their powers?

GG: I think there is more scrutiny of bodies like the TID since 2015. More scrutiny means less space for impunity, which ordinarily translates into marginal improvements in treatment of suspects. The work of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, in particular, in reporting on the abuse of suspects in custody – not only in the context of arrests under the PTA, but in all types of arrests – has ensured greater public scrutiny of law enforcement. I also think the PTA is resorted to a lot less frequently. There have been only a few arrests and detentions under the PTA since 2015. But has there been real systemic change? That is doubtful. The shift in how law enforcement deals with crime in Sri Lanka has yet to take place. We have a long way to go.

HSA: In the absence of specific counterterrorism laws, in what might be called a ‘libertarian’ criminal-justice regime, wouldn’t the government still employ executive bodies like the TID or the army to violate civil rights of individuals? How can those rights be protected?

GG: Yes, that is possible. Problems in coercive interrogations, custodial killings and denial of access to legal counsel are systemic in nature and require a difficult, long-term reform process. Repeal of repressive laws is just one step of many. Prosecuting state officials who commit abuses, instituting better disciplinary procedures, and training law enforcement officials are some of the other measures that need to be pursued.

HSA: How receptive do you think the Sri Lankan government has been to criticisms of the CTA by civil-society groups in the country?

GG: I think this government is more receptive towards criticism. So, it will be difficult for the government to enact a new law that attracts a lot of criticism. In fact, it has withdrawn repressive draft laws such as the amendment to the Penal Code it attempted to introduce in late December 2015 to bring in a new offence on hate speech, and the Criminal Procedure Special Provisions Act, which denied suspects the right to access legal counsel under certain circumstances. These repressive drafts were withdrawn following objections from civil society and the Human Rights Commission.

HSA: Despite all criticism, it seems unlikely that the proposed CTA will be substantially transformed. If the drafted bill cannot be abandoned, do you think it can be improved upon?

GG: I prefer not to answer this question. To be frank, the structural problem in terms of legal certainty will remain with any CTA that contains a special procedural regime. That cannot be remedied except by introducing a very different law – one that only sets out the offences in a clear and precise manner, and contains all the procedural safeguards of ordinary law.

~ Gehan Gunatilleke is a human-rights lawyer and a doctoral student in law at the University of Oxford. He is also a research director at Colombo-based Verité Research. His research and advocacy focuses on media freedom and ethno-religious violence.

Taken from Himal SouthAsian