The 19th amendment was part of a promise to abolish the system of Executive Presidency. Apart from reducing the number of years in a Presidential term from six to five, one of the notable aspects of the 19th amendment was the re-introduction of the two-term limit – any candidate who had successfully won the Presidency twice could not contest for a third time.

The two-term limit came under scrutiny last week, with reports that the Joint Opposition was considering putting forward former President Mahinda Rajapaksa as their candidate. The logic was that the 19th amendment was prospective, and so would only apply to current and future Presidents. It was discussed that the matter could be brought before the Supreme Court.

MP Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne disagreed with this analysis. A more compelling argumentwas put forward by Dr Nihal Jayawickrama, who contended that the powers, functions and duties of the new office of President was fundamentally different from its predecessor – the two offices were distinct and separate.

On August 20, SLPP MP Namal Rajapaksa toldGroundviews during a live Facebook Q and A that he was sure the question on the 19th amendment would be settled in the Supreme Court. Rajapaksa added that in his view, the 19th amendment was a “politically motivated” piece of legislation. This was an odd statement to make, given that Rajapaksa had been one of those who voted in favour of the 19th amendment. There was no mention on his social media or blogof any misgivings – even though he had been vocal around, for instance, issues pertaining the Budget around the same time as the 19th amendment was being read in Parliament.

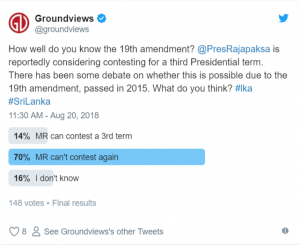

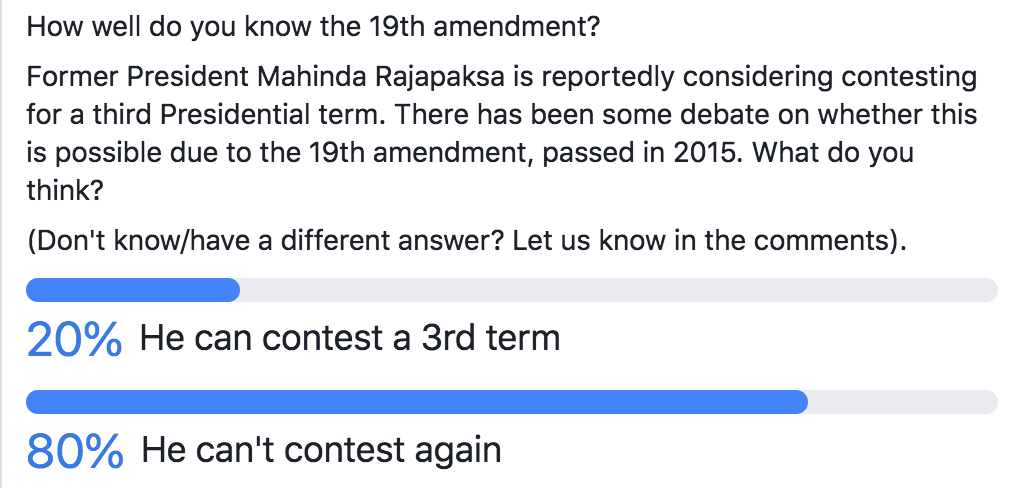

Groundviews posed a question to its followers on Twitter and Facebook, asking if they thought the former President could contest again. The answers were revealing.

On both Twitter and Facebook, the majority felt that Rajapaksa would be ineligible to contest again. On Twitter, 14% felt he could contest again, while 20% on Facebook said the same. This was of course, representative only of the thoughts of Groundviews’ followers who participated. As was cannily pointed out, the polls were more likely to indicate what people preferred, rather than an objective response.

More telling was the number of respondents on Twitter (16%) who said they didn’t know. It is impossible to determine whether the confusion stemmed from the varied interpretations put forward around the two-term limit, or from simply not being conversant with the 19thamendment – but it was certainly telling of confusion around the contents of what remains an abstract document to many.

Those who spoke to Groundviews around the two-term limit contested the view put forward by Dr Jayawickrema, as persuasive as it might have seemed at first glance.

Legal Director at Verite Research, Gehan Gunatilleke said that in his view, the two-term limit did apply to all those who held the office of President under the 1978 constitution.

“At no point in the Amendment is there a reference to the replacement of the office of the President. It is inadvisable to read a specific legislative intent into the text of the Amendment when no such intent is apparent in the actual text,” Gunatilleke said. He added that he had been unable to find any supporting evidence of such intent even in the Parliament Hansard. The Supreme Court’s determination on the 19th amendment made it clear that the President was the ultimate repository for the executive power of people, and any amendments changing this structure would render the amendment inconsistent with articles 3 and 4 of the Constitution. If the amendment had replaced the prior office of President with a new office, this would have to be noted by the Supreme Court, who would have to declare the amendment inconsistent with articles 3 and 4, Gunatilleke said.

CPA Researcher and attorney-at-law Luwie Ganeshathasan pointed out that the amendment was precisely that – an amendment, and not a new constitution. Similarly, the 19th amendment changed the powers of the office of the President, rather than creating a new office. It was telling too that a referendum had not been called – “Can the Supreme Court which said that the 19th amendment as a whole didn’t require a referendum, now say that a new office of the President was established?” Ganeshathasan asked.

In a comprehensive response, Lecturer in Public Law at the School of Law, University of Edinburgh, and the Acting Director of the Edinburgh Centre for Constitutional Law Dr Asanga Welikala pointed out the absurdities of reading intent into the method used to draft the 19thamendment (i.e. the choice to repeal and replace, rather than simply amend).

“Aside from changing the duration of the presidential term, the other difference between the old and new Article 30 is that the latter drops the comma after the word ‘Government’? What are we to make of this? Is this a mere lapse, or is something more sinister going on?” he asked. Dr Welikala also noted that, as was apparent from examining relevant case law, it was not simply a matter of identifying legislation as retrospective or not retrospective – the final rule was far more flexible in application. “We would not be setting out to protect the general interests of society as a whole, or even the rights of a substantial section of citizens, if we are to hold that Article 31(2) cannot have retrospective effect, but the political rights of a very small group of individuals who have been twice elected to the presidency. That number currently is two persons – Mrs Kumaratunga and Mr Rajapaksa – out of a population of 20,359,439 Sri Lankans, and it is not ever likely to be more than a handful of persons,” Dr Welikala said.

A similar view was held by Regional Researcher for South Asia, Amnesty International, Thyagi Ruwanpathirana:

Senior Lecturer at the Department of Public and International Law, Dinesha Samararatne also said that in her view, Dr Nihal Jayawickrema’s interpretation was contrary to the view of the Supreme Court in the Special Determination on the 19th Amendment.

On August 2, at the first Joint Opposition rally, one name was repeatedly mentioned. “Despite the defeat, Mahinda Rajapaksa is our leader!” the speakers on the podium shouted. At the time, this focus on the former President was surprising, given that he would be barred from contesting due to the two-term limit. In hindsight, perhaps this was deliberate. On August 26, Election Commission officials have dismissed the possibility of a successful case to lift the two-term limit, calling the entire saga “unwarranted.”

Perhaps the more interesting question is why this move was contemplated in the first place, and what this means for the Joint Opposition’s strategy to put forward a Presidential candidate.

Political analyst Professor Jayadeva Uyangoda said that the Joint Opposition was clearly launching a campaign for political reasons to involve the judiciary in an essentially political matter, calling the debate a ‘non-existent legal issue’. “These judges know that they are under severe public scrutiny, nationally and internationally. In highly politically sensitive cases like the one that the JO might force on the judiciary despite the clear provisions in the Constitution, the judges will also be conscious of the institutional integrity of the judiciary.”

The recent determination on the issue of President Sirisena’s own term of office showed that the Supreme Court could steer away from narrow political controversies created by politicians to serve personal agendas. “Cases like these are also test cases for the judiciary about its own commitment to protecting liberal constitutional values in a context where they have been under severe threat. The Judiciary might not want to be a party to an exercise that will roll Sri Lanka’s democracy map backwards,” Professor Uyangoda said.

Team Leader – Politics at Verite Research, Shamara Wettimuny noted that the recent legal debate on the two term limit has transformed an internal Joint Opposition conversation about who should be the 2020 presidential candidate into a public debate.

“The question to ask is who benefits from this shift? Shifting the conversation into the public sphere can function as a litmus test on who the appropriate Joint Opposition candidate ought to be,” Wettimuny said.

“On the one hand, it can assess whether there is public appetite for Mahinda Rajapaksa to contest for a third term. For the pro-MR camp, the debate on his eligibility is then only a means of assessing this public appetite and dissuading competitors. On the other hand, for those supporting an alternative candidate, clarifying Mahinda Rajapaksa’s ineligibility at this early stage could clear the path for this alternative.”

Although the younger Rajapaksa seemed confident during his Q and A on Facebook, it is interesting that there has been relative silence from the Joint Opposition since. Perhaps the results of this litmus test will surface at the next, larger Joint Opposition rally, slated to be held September 5.

Editor’s Note: Also read “The Legality and Legitimacy of Presidential Term Limits: A Response to Dr Nihal Jayawickrama” and “The 19th amendment and the future of Sri Lanka“

Taken from Groundviews