Taken from DailyFT

From left: Verite Research’s Research Director Subhashini Abeysinghe, Analyst Hasna Munas and Economic Research Team Leader Vidya Nathaniel – Pic by Ruwan Walpola

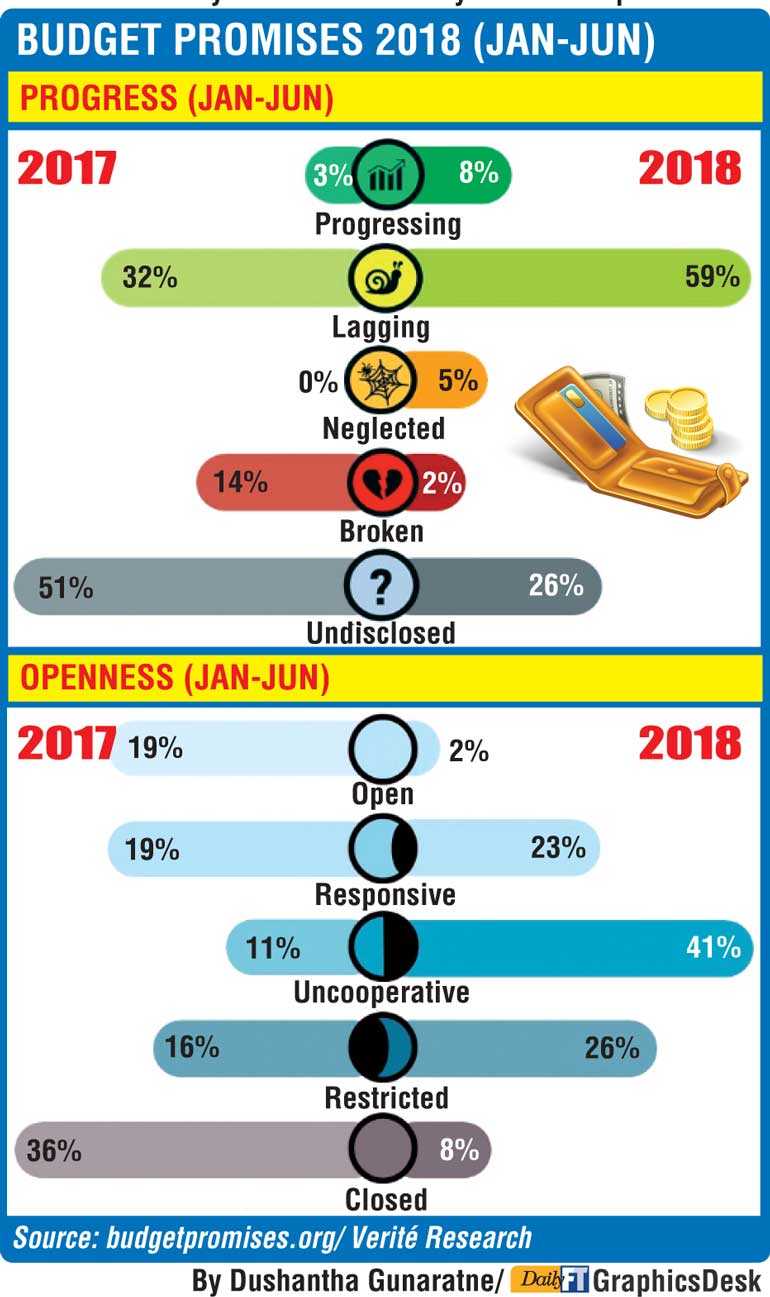

- Verité’s latest Budget tracker for 1H shows only 8% of 38 major proposals worth Rs. 149 b on track

- 33% of proposals tagged as broken, neglected or stalled

- Transparency declines, progress on 74% of promises either undisclosed or hard to obtain

- Lagging proposals include agri loans, farmers’ pension scheme, establishment of development bank

- Progress on proposals worth Rs. 45 b undisclosed, including education reforms, urban regeneration, rural roads

- Concerns raised over Finance Ministry’s ability to monitor Budget

- Confusion over fate of Budget Implementation Unit under Fin. Min.

By Uditha Jayasinghe

Budget 2018 has failed to deliver on transparency and implementation with only 8% of 38 major proposals worth Rs. 149 billion on target, with 33% categorised as either broken, neglected or undisclosed, think tank Verité Research said yesterday.

Releasing the latest ‘Budget Promises: Beyond Parliament’ update, Verité Research tracked 38 proposals, which were allocated above Rs. 1 billion in Budget 2018, for the first six months of 2018. Their research found there has been little improvement in implementation when compared with Budget 2017 and Budget 2018, with transparency actually declining for the latter. The bulk of new expenditure proposals in Budget 2018 were also categorised as lagging in implementation.

“While the Government’s progress in implementing its Budget promises remains stagnant, its willingness to disclose information has declined. In the first half of 2018, information on progress for 74% of the tracked promises were either not available or obtained with difficulty,” said Verité Research’s Research Director Subhashini Abeysinghe.

Only three proposals were on track. They were a Rs. 17.5 billion project to provide 20,000 housing units under the Urban Regeneration Project by 2020 for the poor by the Megapolis and Western Development Ministry, a Rs. 2 billion skills development program by the National Youth Corp and a Rs. 1.7 billion fisheries habour development project by the Fisheries Ministry.

As much as 59% of the proposals were tagged as lagging. These include significant projects such as the Rs. 3 billion Aruwakkalu waste disposal site, Rs. 5.3 billion in concessional loans to agri companies to improve technology infusion, Rs. 3 billion for a contributory pension scheme for famers, Rs. 10 billion for the establishment of a development bank and Rs. 3 billion for building houses in the north and east. The Central Expressway project was also marked as lagging by Verité Research.

Among the undisclosed proposals, which amounted to Rs. 45 billion, were a slew of projects including Rs. 3.5 billion allocated for education reforms, Rs. 1.25 billion for medical faculties at the Wayamba, Sabaragamuwa and Moratuwa universities, Rs. 5 billion to expand the availability of technology degrees, Rs. 24 billion for urban regeneration projects and Rs. 2.5 billion to improve the rural road network.

Two promises were slotted into the neglected category accounting for Rs. 12.5 billion. These were the proposals to establish an EXIM Bank with Rs. 10 billion, which was included in Budget 2016, 2017 and 2018 as well as a plan to create an employment preparation fund.

In nearly 60% of the promises being tracked, Government institutions failed to provide the action plan or progress report in response to requests filed under the Right to Information (RTI) Act. Further, only 33% of progress reports could be compared against the action plans received, Verité Research said.

Even though a few Government agencies were cooperative, many others were less so, leaving the researchers dependent on few resources. The Irrigation and Water Resources Ministry, Fisheries Ministry and Housing Ministry were the three most transparent while the ministries of Agriculture, Education and Highways were the most opaque.

Verité highlighted the importance of one report released by the Department of Project Management and Monitoring, under the Youth Affairs and Project Management Ministry, to improve transparency.

“This does not cover all the Budget proposals but it was useful to make an assessment. The report gave us details on what happened in the first quarter of this year. Without this report the undisclosed component, which is currently at 26%, would have gone up to 42%. It underscores the fact that the public does not know when proposals are changed or not implemented. Where does the money go in such instances? Is the Government reluctant to tell us what it is doing? If the Government cannot implement a proposal that is fine but it needs to give reasons and explain to the public. It should not be kept hidden,” said Verité Research Economics Team Leader Vidya Nathaniel.

The researchers pointed out that the information requested from the Government agencies should be compiled under circulars issued by the National Budget Department under the Finance Ministry but even though the circular was released in January 2017 giving specific formats to be followed on the mode of submission and timelines, few agencies had complied.

“Of the 38 proposals that we were tracking only 50% had action plans or progress reports that were released by the relevant agencies. So this is a concern. Even of the action plans or progress reports we received only a third of their plans aligned, which means that the activities listed under the action plans actually aligned with the activities listed under the progress reports. In several instances it was very difficult to understand what the different documents were attempting to convey,” she added.

Verité emphasised that the level of openness of a particular agency could be linked to the level of project implementation. They opined that research suggested the higher the implementation level of proposals the more agencies were keen to share the information. If implementation was low transparency was also likely to be lower.

Sometimes these traits were displayed by the same entity. For example the Megapolis and Western Development Ministry, which was cooperative on one project of providing 20,000 houses, was nonetheless more restrained on five other major proposals, which accounted for over Rs. 24 billion.

“The transparency of agencies varies to a great extent and raises questions of whether the Finance Ministry is actually able to do its job of monitoring Budget proposals if they are not getting the information as necessary. We asked the National Budget Department what ministries have given documents as specified in their circular and we found out only two ministries, Buddha Sasana and Foreign Affairs, had done so. Only the Buddha Sasana Ministry had given a disbursement plan and none of the 59 Government agencies had a strategic plan for policy proposals,” Nathaniel said.

“It is possible that the documents were given in different formats but the challenge for the monitoring process remains. Is the Finance Ministry doing its job? Part of the responsibility is to monitor physical and fiscal progress but in the RTI submitted to the Budget Department we were told that it does not monitor fiscal progress and asked us to find out details from the ministries ourselves, so then if they are not monitoring it who is? Why is there a circular for this information if they are not monitoring it?”

Verité Research recalled efforts last year by Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera to establish a Budget Implementation Unit under the Ministry. Subsequently, the national Budget Department issued a circular saying that such a unit was formed to monitor capital projects including proposals but when information was requested by Verité the response stated no such unit was established under the department.

“We find this very surprising because under a separate RTI the same department told us to refer to the very same Budget monitoring unit. So you can see the contrast. The RTI responses were even signed by the same person. The reluctance to share information could cast doubt on the budgeting process as a whole and that makes the public lose confidence in the whole system.”