Taken from – Sunday Observer

Photo Courtesy – Sunday Observer

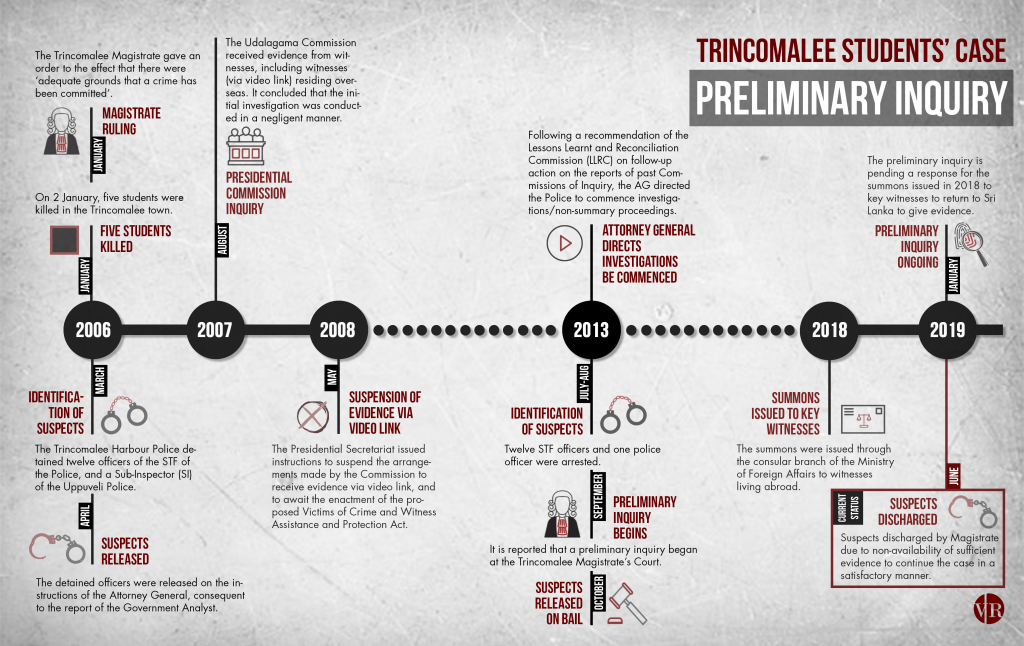

The dismissal of 13 security forces personnel by the Trincomalee magistrate, could mark the end of the road in terms of achieving justice for the five young boys brutally slain on a beach in Trinco town 13 years ago, unless new evidence surfaces. The inability to locate witnesses to testify hampered the investigation by the CID, and rights activists say the case highlights the failure of Sri Lanka’s justice system to hold the security forces responsible for crimes

On July 3rd nearly five years after the Magisterial inquiry into the murders of five youth from Trincomalee in January 2006 commenced, the Trincomalee Magistrates Court dismissed all 13 law enforcement personnel who had been accused. One of the most emblematic cases in the East during the country’s long drawn out conflict, had eventually ended without justice being served. 12 Special Task Force (STF) personnel and one policeman who were named as suspects in the case, walked free on the day.

The Criminal Investigations Department (CID) had not been able to provide any evidence of significance and were also unable to present several key witnesses in courts. The CID claimed that they were unable to locate the two survivors of the incident and the father of one victim, medical doctor Kasipillai Manoharan, (now a refugee in the UK), hence the case was adjourned several times over a time period of five years. Despite offers to Dr Manoharan to testify via video from the Sri Lankan High Commission in London, these overtures were turned down by him , citing security concerns. As a result, the Chief Magistrate was forced to release the suspects due to the lack of evidence. However, the Trincomalee Chief Magistrate M.M Hamza also noted that the discharge of the accused will not prevent the Attorney General from reinitiating a Magisterial Inquiry if new evidence is discovered.

Whilst all hopes seemed to have faded for the families of the victims, Attorney General Dappula De Livera this week wrote to Acting IGP Chandana Wickramaratne, directing him to take necessary action to locate three key witnesses in the case, in a bid to ensure that justice is served. However, the recent move of the Attorney General brings little solace to the father of Ragihar Manoharan who was killed on that fateful day. “I have no confidence that justice will be served even though the Attorney General has given such directions,” says Dr Kasipillai Manoharan. He said the Sri Lankan justice system has continuously failed to deliver justice to the Tamil people in Sri Lanka. “Even if directions have been given, it may take another 10 years” he added.

The justice he seeks is far different to what the government of Sri Lanka has to offer.Instead seeking justice from the international judicial system, Manoharan says he would not be able to call himself the father of Ragihar if he does not achieve justice. Since 2006 Dr Manoharan has been fighting an almost lone battle, forced to flee the country, and living far from his hometown of Trincomalee where the horrific killing of his son took place.

But post-war Trincomalee is deceptively quaint and serene. On any given day of the week, the beachfront adjacent to the Gandhi roundabout, a popular hangout spot for its locals and tourists alike, is often brimming with beachgoers and vendors. But nearly 13 years ago the white sands of the beach witnessed some horrific and sinister incidents. On January 2, 2006, five boys including Ragihar were killed, allegedly execution style, on this beach. Only two from the group of friends escaped alive. The incident became one of the first so-called “emblematic” crimes, committed between 2006 and 2009, when the war finally ended. The boys were allegedly executed just two months after President Mahinda Rajapaksa was swept to power in the November 2005 presidential poll.

Ragihar and his friends Yogarajah Hemachchandra, Logitharajah Rohan, Thangathurai Sivanantha, Shanmugarajah Gajendran, Yoganathan Poongalalogan and Prarajasingham Kowulraj all just 20 years of age had gathered at the beach that night to mark the New Year.

According to Dr Manoharan, he had received a strange text message from his son on the night which merely read ‘Dad’. Ragihar then calling his father had claimed the security forces had surrounded them, before the line went dead. Later the residents heard an explosion from the beach front. Manoharan had rushed to the scene but was prevented from entering the area by a Naval cordon. “I heard cries for help in Tamil” he recalled adding that he then heard gunfire.

Visiting the mortuary later Manoharan had to identify the bullet-riddled body of his son. “The first body they showed me was of my son,” he said. Officials at the time claimed Ragihar and his friends had died when a grenade carried by them exploded. The truth only came out when the District Medical Officer Dr Gamini Gunatunga bravely confirmed that the youth had been shot dead. But Ragihar and his friends were labelled as LTTE militants by the authorities, an accusation vehemently denied by Dr Manoharan.

“He was a quiet and good child,” says Dr Manoharan speaking of his son Ragihar. A coach in the Table Tennis Association, Ragihar had aspired to be a doctor like his parents. “Everything got ruined,” the inconsolable father said.

The incident drew a huge outcry among human rights groups calling on the government to bring to justice those killed in the incident. But many incidents of intimidation following the killings have left Dr Manoharan with a visibly deep-seated fear of Sri Lankan law enforcement authorities, and mistrust of the country’s legal system.

In 2006 Dr Manoharan was the only witness to testify. However, he and his family faced continuous intimidation and harassment. When an inquest was held on January 10 days after the killings, Manoharan testified. That night his house was pelted with stones, and he received several anonymous calls that night and on several subsequent nights. A man speaking in Sinhala mixed in with a few words of Tamil threatened to kill him and his family. The offence which earned the anonymous caller’s wrath was that he had testified at the inquest against those who had killed Ragihar and his friends.

However, despite the threats, Dr Manoharan arrived at the Trincomalee Magistrates Court the following week with several other witnesses who had since stepped up, only to be called ‘Kotiyas’ (Tigers) in a reference to the LTTE by a Policeman who was in Court.

In June that year, the brother of the slain Ragihar, Sharhar Manoharan was stopped by two Policemen in Trincomalee while he was on his way to sit for his Advanced Level examinations. Ascertaining he was the son of Dr Manoharana the Policemen had remarked, “Your father is flashing this whole matter in the international stage.This is not good. We will see you later”. Taking this as a threat Sharhar had returned home instead of going on to school. Eventually, Manoharan had to give up his medical practice and his children had to stop attending school. He eventually had to flee the country, and was granted asylum in the UK.

He was not the only witness to face severe consequences – weeks after the killings, Sudar Oli journalist Subramaniyam Sugirdharajan was shot dead. He had accompanied Dr Manoharan to the mortuary and published photos showing the bodies with point-blank gunshot injuries, disproving government claims that they were killed by a grenade explosion. A witness to the case, a three-wheeler driver in the area suffered a similar fate.

According to Dr Manoharan, a Buddhist priest who publicly condemned Ragihar’s murder was also killed. Handungamuwe Nandarathana. The monk, who spoke Sinhala and Tamil, had worked towards peace and had attended both a memorial for the slain students, as well as Pongu Thamil events. He was shot dead by gunmen in May 2007. The apparent inaction against those who held commanding positions at the time has also proved problematic. With another discussion at the Human Rights Council scheduled for September 2013, just months ahead on July 12, STF officers were arrested in connection with the case. However, Human Rights activists at the time, criticized the government’s failure to arrest Kapila Jayasekara, the former head of the STF (Trincomalee), whom local human rights monitors traced to the murder scene. In August 2013 the government promoted Jayasekara to the rank of DIG and sent him back to the Eastern Province. Today he is the Senior DIG in charge of the province.

Meanwhile, adding insult to injury, even those arrested were released on bail, in just a few months. The majority of them even continues to be in active service. A 2008 report by the University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR) notes, “At the core of these crimes in Sri Lanka is the endemic refusal of the rulers to move from criminal responsibility to command responsibility.

This means that however grave a crime, a few from the lowest ranks of the security forces are brought to court for carrying out the wishes of their superiors, and inevitably the public feels sorry for them…..The country has learnt to be comfortable with grave crimes going unpunished one after another, with the certainty that even graver ones would follow”.

As a result of these lapses, local officials have failed to gain the trust of Dr Manoharan and other witnesses. To obtain key evidence from Dr Manoharan in courts, in 2017 the government using the Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act, said he could provide evidence in the case before a local court through Skype. However, according to the amendment a witness can only provide such evidence at a Sri Lankan diplomatic Mission office.

This was a term, Dr Manoharan was not agreeable with. The notion of visiting the Diplomatic Mission had made him uncomfortable. As a result, Human Rights Organizations called for further amendments to the law, taking into account all concerns that victims may have to ensure that those like Dr Manoharan have a genuine opportunity to provide unfettered evidence.

As Dr Manoharan was not given the opportunity to provide evidence through satellite technology from a location where he feels safe, the CID lost the chance to provide vital evidence to the courts resulting in this most recent outcome. But according to Dr Manoharan, the lack of evidence should be blamed on the CID.

“They did not conduct proper investigations” he accused, adding that there are a number of witnesses in the country and abroad other than himself, whom the CID had failed to trace.

But despite the setbacks, Dr Manoharan has sworn to continue his fight for justice.

He is adamant that the case is heard in either at the International Courts of Justice or in a Hybrid Court. “Only then victims and witnesses will come forward to provide evidence and have trust in the system”.

According to Yolande Foster (now an independent researcher who was previously with Amnesty International, working for victim families) last week’s development came as a bombshell shattering their faith in Sri Lanka’s criminal justice system.”The failure to deliver the ‘right to truth’ in (extreme) cases like the Trinco 5, highlights the failure of Sri Lanka’s justice system to hold the security forces responsible for crimes,” Foster noted.