Published on Daily Mirror

Sri Lanka’s problem is not that it does not have a law in place, but that despite the legal obligation that exists for public authorities to disclose information, there is a lack of compliance with the law

Today (28 September) marks the international day for universal access to information. This year’s theme is ‘the importance of the online space for access to information.’

Public access to information is an essential element of a functioning democracy. It can promote public accountability for government decisions and thereby, also combat corruption. This idea is echoed in the preamble to the Right to Information Act, No. 12 of 2016 (RTI Act), which emphasises the need for transparency and accountability of government in order to enable the people of Sri Lanka to fully participate in public life, combat corruption and promote good governance. The RTI Act enables the public to access information: (a) by the public requesting information from public authorities and (b) through public authorities providing certain types of information to the public, i.e. proactive disclosure. Article 14A of the Sri Lankan Constitution also guarantees the right of access to information.

Sri Lanka’s problem is not that it does not have a law in place, but that despite the legal obligation that exists for public authorities to disclose information, there is a lack of compliance with the law.

The findings of Verité Research’s 2022 assessment released earlier this month on online proactive disclosure under the RTI Act, demonstrate that the government has a long way to go to fully comply with their obligations under the Act.

Figure 1

Figure 2 Figure 2 |

Verité Research looked at proactive disclosure requirements under the RTI Act. The assessment monitored whether public authorities: (1) disclosed information online as required by the Act; and (2) whether that information was usable, which included the availability of information in all three languages (Sinhala, Tamil, English). Accordingly, public authorities were placed into five levels based on their score (Figure 1).

Marginal Progress from 2017 to 2022

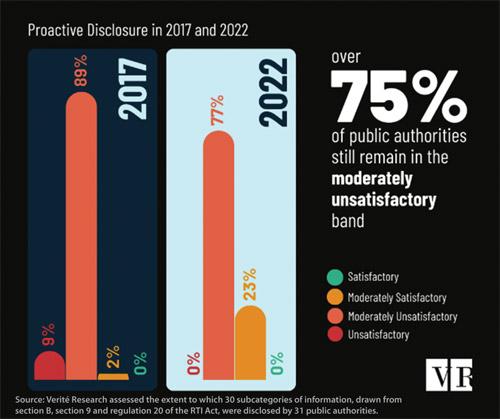

This is the second time that Verité Research has conducted this assessment — the first time was in 2017. Compliance with the RTI Act has seen only marginal improvement over the last 5 years, indicating that public authorities are not prioritizing compliance with proactive disclosure requirements under the law. In 2017, 89% of public authorities were considered, on the average score, to be moderately unsatisfactory. Yet, 5 years later there are still 77% of public authorities who continue to fall within the ‘moderately unsatisfactory’ level – meaning that they disclosed less than 40% of the information legally required on their websites (Figure 2). Although there has been marginal progress over the last 5 years on compliance, most public authorities still scored low when looking at their compliance with the Act.

Even the highest performing public authorities from the 2022 assessment – the Ministry of Agriculture (at 57%) and the Ministry of Public Administration (at 53%) – scored just over 50%.

Figure 1

Where there is a will- there’s a way

The assessment scores public authorities based on 11 categories and 30 sub-categories of information. Verité Research found that in some categories of information, public authorities have scored well, demonstrating that compliance is possible. For example, under the specific requirements of Section 8 of the Act – which places a duty on every minister to publish a report containing information relevant to their ministry – the Ministry of Public Administration scored 81%. In terms of requirements under Section 9 of the Act – which requires ministers to inform the public about the initiation of a project three months prior to its commencement – the Ministry of Agriculture scored 68%.

Additionally, when looking at disclosure in all three languages, the assessment revealed that out of the 31 public authorities, only the Office of the President and the Ministry of Wildlife consistently published information in all three languages. Public authorities, in general, disclosed nearly half of the information in English, while they disclosed only 37% in Sinhala and only 29% in Tamil.

Lack of capacity or inertia?

This demonstrates that compliance with proactive disclosure is possible, and it isn’t always a matter of a lack of capacity, but perhaps inertia. If the Office of the President and Ministry of Wildlife can disclose information consistently in all three languages, then other public authorities should be able to as well.

Public authorities provide various reasons for why they find compliance challenging. However, when we compare the scores of public authorities against each other, it seems that the primary requirement for public authorities to improve compliance is straightforward – a willingness to share information.

Nishana Weerasooriya currently works as a Senior Research Manager for the Legal Research Team at Verité Research. She is a lawyer licensed to practice law in New York.

Shannon Talayaratne currently works as a Junior Research Analyst for the Legal Research Team at

Verité Research.