Last Thursday, November 23rd, university economists and their invited guests gathered at the Rajarata University of Sri Lanka (outside Colombo) to hold the annual conference of the Sri Lanka Forum of University Economists (SLFUE). Dr. Indrajit Coomaraswamy, the Governor of the Central of Sri Lanka graced the occasion as the Chief Guest, while Dr. Fredrick Abeyratne, former Head of Poverty and Governance Unit of UNDP delivered the keynote speech.

Government and People

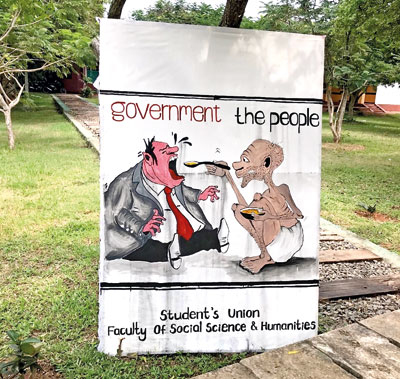

There were posters and flags either side of the way to the conference venue.

My attention was caught by an Internet cartoon on a poster, leaning on a tree by the roadside (see picture). It depicted a kind of a government-people relationship with a portrait of people feeding the government. The panel discussion followed by the inauguration formalities, had important bearings on the message of the poster.

The panel discussion was on “Balanced Economic Growth of Sri Lanka” and the “Challenges and Reforms”. Balanced growth means different things to different people.

At the outset economist Subhashini Abeysinghe, who moderated the discussion, introduced some of the basic differences in opinion: growth must benefit all not just some; growth must leave resources and opportunities for future generations; growth must go even beyond wealth accumulation. However, the panel discussion progressed on the first.

Inherently Imbalanced

I appreciate what Sumanasiri Liyanage, a former Professor of Economics emphasised at the discussion: “Capitalist growth is inherently unbalanced”.

However, I am not convinced yet, if there is any better way other than the capitalist way which depends primarily on private investment guided by the market and the private property. Neither did he mention any alternative to the capitalist way. It is the capitalist system that reproduces seeds of economic growth, but it is true enough it has never been balanced anywhere in the world.

English economist J.M. Keynes in his 1939 seminal publication in 1939 – General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money did not make an explicit attempt to balance growth; but effectively it did in some way or the other.

His contribution was mainly to sustain capitalist economic growth by smoothening its periodic recessions by assigning a major role to the government. Capitalist growth is also inherently cyclical with booms and busts; the latter produces ingredients to overthrow capitalist systems through shrinking output, falling income and, rising unemployment.

Letter to Bernard Shaw

Keynes, in a personal letter wrote in 1935 about his forthcoming book to his Irish friend, Bernard Shaw – the famous contemporary play writer:

“When my new theory has been duly assimilated and mixed with politics and feelings and passions, I cannot predict what the final upshot will be in its effect on actions and affairs, but there will be a great change and in particular the Ricardian Foundations of Marxism will be knocked away. I can’t expect you or anyone else to believe this at the present stage, but for myself I don’t merely hope what I say. In my own mind I am quite sure.”

This letter is no more personal, as it has been published in some economic textbooks and papers. As this passage quoted in that letter implied, Keynes knew that his publication in due time would knock down Marxism. Basically, what the General Theory of Keynes suggested was the way to sustain aggregate demand through fiscal policy – a policy tool that the government has in hand to become stronger when the private spending is weaker in recessions. For this reason, even today at recessions, governments turned out to be “Keynesians” with increased spending, financed through borrowings and money printing.

In countries like Sri Lanka, however, reckless government spending has gone out of control, not because our politicians know about Keynesian economics; but it is the ideal mixture of the worst things that wrongly believed to have made them better off at the expense of people – unbalanced growth. I must say that this imbalance is the recipe for disaster for both parties – the government and the people.

Regional Imbalance

Growth is unbalanced in many ways. P.C. Madduma Bandara, a former Professor of Geography, brought about an important dimension of unbalanced growth by referring to regional growth imbalances in Sri Lanka. Growth has concentrated in the Western Province where over 5 1/2 million people (29 per cent of total) live in 6 per cent of the land area, producing over 40 per cent of total GDP and earning US$5,690 per capita GDP (2016).

Growth has never been even across geographical space. What we usually find is that growth and people both get concentrated in smaller locations of a country, leaving larger areas as farm lands and forests. This is because, from a business point of view, investors find it advantageous to locate their businesses in compact locations rather than spreading them everywhere.

People also follow the suit. They find better opportunities in the same locations to make use of their human resources productively (better work) and to derive benefits of growth (better life). The faster the growth process, the greater will be spatial concentration of growth and people.

The government cannot push economic growth on the shoulders of people to their desired locations. Infrastructure is one important thing, but spatial growth is shaped by many other economic conditions. Fundamentally, growth has to be rapid enough producing spillover effects, markets have to be large enough allowing economies of scale, and the location has to be open enough strengthening local and global connectivity. Neither of these can be achieved unless and until the business environment for private investment is competitive and efficient. It is not for any ideological reason, but it is the private investment that drives growth momentum.

Safety Zone

Markets work for efficiency and not for equity and inclusiveness so that it is not wise to anticipate balanced growth whichever the way we define it.

Because growth based on efficient markets does not necessarily guarantee a socially, politically or environmentally desirable outcome, there is always space for arguments for a desirable growth outcome. But what is important is that efficient markets produce wealth and opportunities to handle equity and inclusiveness.

Therefore, the whole debate over balancing growth is not about paralysing the markets damaging growth, but about setting boundaries without compromising on competition and efficiency.

A clear distinction between efficiency and equity needs to be maintained in policy-making. What it means is that by prioritising a desirable outcome, policies should not undermine growth. Mixing efficiency and equity objectives would achieve neither of them. Mixing economic and political objectives can be disastrous in the long-run.

Mixing economic and social objectives can undermine the anticipated outcome of both. These are instances where policy attempts for “inclusive growth” can go wrong.

(The writer of this weekly column in the Business Times dealing with economic issues is Professor of Economics at the Colombo University)

Taken from – Sundaytimes.lk