The Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) is the largest single fund in Sri Lanka. In 2017, it held over LKR 2 trillion in employee savings. The EPF is a mandatory retirement savings scheme. This means private sector workers must contribute to the fund regardless of the returns they receive. Therefore, the EPF’s investments and returns concerns both the social security and justice for much of Sri Lanka’s working population.

The EPF’s investments are managed by the Central Bank. Since the initiation of the fund in 1958, it has almost entirely invested in government securities. Yet, from 1998 onwards, the EPF also started investing in equities, mainly via the stock market. Initially, its exposure to equity was minimal, i.e. below 1.5%, However, from 2010 onwards, the EPF increased its equity exposure to over 5% of the fund.

Since 2009, the EPF has taken equity investment decisions that have been severely detrimental to the fund. Concerns raised about the EPF’s management in Parliament from 2013 onward led to restrictions on its equity investments for several years. In October 2018, the Central Bank announced that it would once again expand the EPF’s investments in the stock market.

This Insight shows that the two reasons provided by the Central Bank for doing so, are analytically flawed. Consequently, the retirement savings of workers is under a renewed risk of being compromised.

EPF: A history of losses through equity investments

As at the end of 2018, 7.8% of the EPF’s current fund value is in investments outside of government securities. A detailed overview of the fund’s current position is not available because of the EPF’s poor track record in publishing timely annual reports – they are usually delayed by over 2 years, and the latest annual report available at present is for 2016.

Previous analysis from Verité Research has shown the EPF’s investment in the share-market to be harmful to the worker’s interest. In 2009 and 2010, EPF returns from equity investments were less than 5% while the share market as a whole, as given by the All Share Price Index (ASPI), was achieving a return of around 100%.

Other equity investments by the EPF outside the share market have also been inimical to workers’ interest. For example, in 2010, the EPF, without due process, invested LKR 500 million in Sri Lankan Airlines. As of 2016, this investment has been 100% impaired in the EPF books (that means, it is now valued at zero). Another such example is the EPF’s investment of LKR 5 billion in Canwill Holdings, for the controversial Hyatt Hotel project, in 2013. Both these investments have come under scrutiny in the Auditor General’s Report in 2016. The same report notes a total impairment loss of LKR 8.1 billion (that is the value written off and lost in the EPF books) from the investments held by the EPF.

As of September 2019, the EPF had a mark-to-market loss of LKR 23 billion on its equity portfolio, with a purchase cost of LKR 83 billion – that is equivalent to 28% loss of the capital invested. According to 2019 Budget Estimates, this amount is equivalent to the cost incurred by the Ministry of Housing to build approximately 46,000 houses.[1] There is no formal audit released to the general public by the Central Bank for the past investment decisions that have compromised the retirement savings of Sri Lankan workers.

EPF’s justification for the investment in equity

It is in this context, of irresponsible investment of EPF funds, and the lack of accountability for those actions, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (the managing authority), in 2019, once again decided to expand the EPF’s investments in the stock market.

The Central Bank has provided two reasons for this renewed policy: (i) to improve the financial returns to the EPF fund; and (ii) because the EPF’s lendable funds are expected to outstrip the government’s demand for borrowing after 2020.

The present Insight finds both these reasons to be analytically flawed. This then suggests that the Central Bank should seek to be transparent and correct in its reasons to expand its equity investments, and would be well advised to reverse this decision to expand investments in equity markets until it is able to justify the move in terms of worker interests.

The equity market does not offer a better return to the EPF

There are two ways to set out (using simple terms) the analytical flaw in the claim that investing in equities would allow the EPF to get a higher return than investing in government securities.

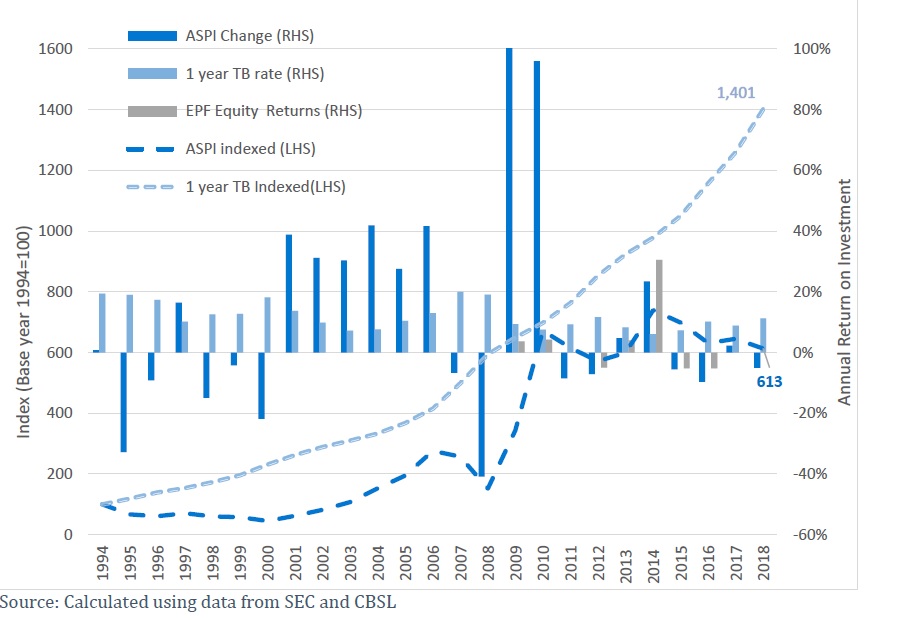

Exhibit 1 shows if LKR 100 was invested in one-year treasury bills and, reinvested together with the year-end returns, every year for the last 25 years, it would have yielded LKR 1,401 at the end of 25 years. However, investing the same amount in the stock market for the same period would have yielded only LKR 613 at the end of the same 25 years. In short, the cumulative rate of return from the stock market is less than half the return from one-year government securities in that 25-year period. Note that this higher return calculated from one-year government securities, in relation to the stock market, is despite one-year securities having lower yields than longer-duration securities, which the EPF would usually purchase.

The second way to set out the analytical flaw is to evaluate the risk-adjusted return of the stock market around the specific high-performance periods. Since every performance period other than the 20-year period had a higher return from government bonds, which also had a higher risk on the stock market, only the 20-year period merits further evaluation.

A risk-adjusted evaluation was made by using Sharp Ratio (the most prevalent method of evaluating risk-adjusted value). For the calculation, the lowest rate of return on government securities during the period was used as the common risk-free rate – it was of 6.01%. The stock market returns had a standard deviation of 40 percentage points against an annualised return of 12.5%. The government securities had a standard deviation of 4 percentage points against an annualised return of 10.4%.

The sharp ratio for the stock market and government securities were 0.16 and 1.05 respectively. A higher sharp ratio indicates a higher risk-adjusted return. Therefore, given the level of risk, for the stock market to have the same risk-adjusted return as the government securities, the average annualised return in the stock market would have had to be 48%, while the observed return was only 12.5%.

This means, that even if there was a possibility of extracting higher returns from the stock market in the short term, long-term investment of the EPF in the stock market is not justified by the level of risk that emerges from the volatility of the stock market returns.

Exhibit 1: Value of investment in Share market and Government Securities, 1994- 2018

Parameters used for the calculations in Exhibit 1.

Parameters used for the calculations in Exhibit 1.

- Share market returns are calculated through changes in (ASPI) – the only index available for a longer period. Returns of the ASPI is similar to that of other indicators such as past Milanka index, and the new S&P 20 index. For instance, the CAGR for Milanka was 11.5% from 1998 to 2012 and ASPI it was 16.2% in the same period. The S&P 20 had a CAGR of 2.9% from 2012 to 2017 while ASPI had 2.0% in the same period.

- The return on government securities is the annual yield on the one-year Treasury Bill.

- For the above comparison, on the stock market, the dividends payments were not considered, and on government securities, the higher returns from longer term securities were not considered either. The All Share Total Returns Index, which includes the dividends, is available only from 2004. This was only 1.5% higher than the returns without dividends, in the available data

- EPF equity returns are calculated from the annual report of the EPF for various years.

Lendable Funds of the EPF will not outstrip government demand for borrowing

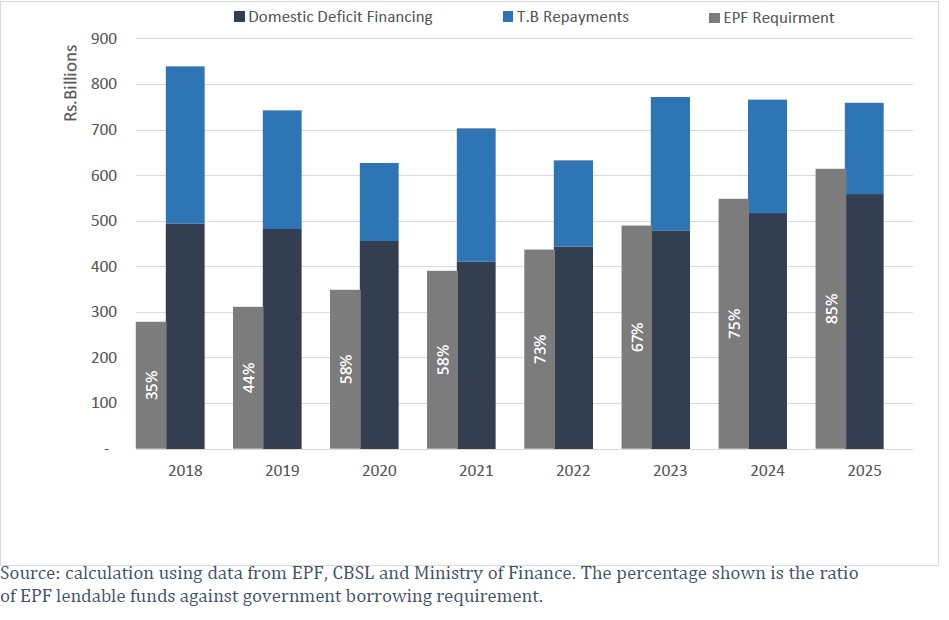

The second explanation by the Central Bank, for moving again into the stock market, is captured in the following quote, from the Monetary Policy Briefing in October 2018

“In the future the government domestic funding requirement will get lower. The domestic repayment is peaking at 980 billion rupees this year, 600 billion rupees next year. After that it’s 500 or 400 billion rupees… Then the opportunity for the EPF to invest in government securities becomes less and the fund is becoming bigger. Then we need to find other opportunities”

Exhibit 2: Increase in government’s borrowing requirements and EPF lendable funds, 2018- 2025

Parameters used for the calculations in Exhibit 2.

Parameters used for the calculations in Exhibit 2.

- 12% growth rate of the EPF lendable funds – this is a relatively high estimate. Trend analysis shows a steady decline in the fund growth rate, which was already down to 12% in 2017

- 5% of GDP medium-term budget deficit target will be achieved and sustained – as per the medium-term debt management strategy

- 8% nominal GDP growth (e.g. inflation at 4% and real growth at 4%) – this is relatively a low estimate. Higher nominal growth will imply higher values of the budget deficit.

- Domestic financing of the budget deficit is assumed to be 65%of the deficit – as per the medium-term debt management strategy.

- Maturing Treasury Bills and Bonds that are not owned by EPF is assumed to be 57% of the total domestic debt maturity – because EPF owns 43 percent of the stock of Treasury Bill and Bonds in 2018.

- This calculation is without counting the additional financing needed for maturing foreign debt – i.e. assumes that requirement will be refinanced from further foreign borrowings.

This claim is also analytically flawed. The Central Bank claim, quite inappropriately, ties the borrowing requirements of the government to the maturity of existing government debt. It fails to recognise the requirements that arise from future budget deficits. Exhibit 2 shows that the government’s borrowing requirement available to the EPF exceeds the EPFs increase in lendable funds for the foreseeable future. This based on adding only what the government has projected to be domestically financed from the optimistically projected Budget deficit, and the maturing domestic debt that is not owned by EPF, and not considering the refinancing of foreign debt.