Elected officials and selected bureaucrats are given a huge amount of power to act on behalf of the public – modern democracies function on this basis: that citizens hand over their power to elected representatives. But how can citizens then protect themselves against those individuals misusing that power? This is the perennial problem of governance. The simple answer that is given to this question of governance, is “elections” – that elections ensure the displacement of politicians who violate the public trust, and thus create political incentives for better behaviour. This Insight provides an example, which explains why the answer cannot be that simple – the behaviour of officials during elections can both abuse public trust, as well as benefit these officials politically. As such, other governance solutions are needed.

Economic model of the governance problem

The principal-agent model in economics is frequently used to analyse the problem faced by citizens with regard to elected officials and bureaucrats. It is the same model that is used to look at the relationship between owners of firms (the principal) and their managers (the agents). The fact that owners can dismiss the managers is not an adequate check on poor management, because the owners must also be able to distinguish bad managers from good managers, and this is often not easy to do.

Managers are governed by ethics and incentives. When the ethics are weak, the incentives become more important. Therefore, owners tend to set incentives that are tied to outcomes. However, there are two major ways in which bad management can camouflage itself. One is that a good external environment can mask bad performance – a rising tide lifts all boats – and another is that visible short term benefits can come at invisible but high long term costs. Inability to make the distinctions results in an improper evaluation of performance, and much of this was evident in the run-up to the Wall-Street financial crisis of 2008.

Governance problem in economic management

This same principle-agent problem exists between citizens and politicians who oversee the financial management of a country. The principal in this case is the citizens.

A previous Verité Insight titled “Exchange Rate, Politics Trumps Professionalism” argued that a professional approach to the management of the exchange rate seems to have been trumped by political considerations in 2015 as well as periodically by successive governments.

This Insight shows that a similar problem exists with regard to fiscal management: elections cycles create incentives for politicians to mislead citizens by exploiting the short-term vs. long-term disjunction: creating short-term benefits at a high long-term cost.

Election cycles have led to worse, not better, fiscal management

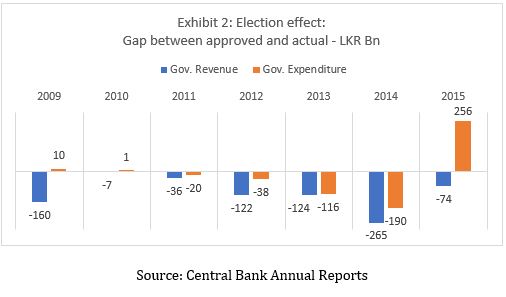

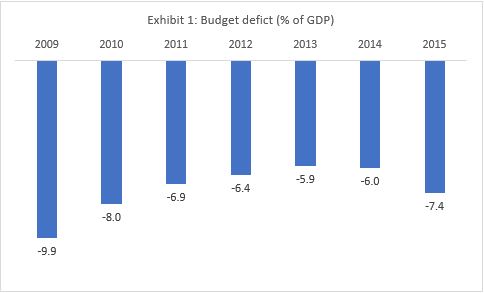

Consider the last two cycles of election: 2010 & 2015. The Presidential and Parliamentary elections were held in January and April 2010 and in January and August 2015. Exhibit 1 shows that governments tend to let budget deficits balloon during election years, giving a false sense of success to voters but often compromising long term welfare and stability in the process.

The long term pain becomes evident when, the price of utilities is increased, health and education is under-funded, assistance to the poor is reduced, taxes are increased and the IMF is brought in to keep things afloat.

In 2015, the government faced a short fall in revenue (from what was budgeted) of 74 billion (Exhibit 2); however, instead of cutting expenditure from what was planned, it increased it by LKR 256 billion and allowed the deficit to expand to 7.4% of GDP (Exhibit 1). Some of this behaviour is reflected in the pre-election year as well. The government in 2009 faced a LKR 160 billion revenue shortfall, but again slightly increased expenditure instead of cutting it; and, allowed the budget deficit to balloon to 9.9% of GDP – the presidential election was in January 2010 (Exhibit 2).

A vicious cycle and unequal distribution of gain and pain

Elections have created a vicious cycle for economic management in Sri Lanka. After binging just prior and during election years, governments then settle down to tightening their belts, and taking measures to enhance revenue. Both demand painful adjustments for the public that is forced to accept lower quality and quantity of public services and/or higher taxes. And, the reserves built by these painful adjustments can be squandered at the onset of the next election.

The gain (in the short term) and the pain (in the long term) are also unequally distributed. It is usually the special interest groups, such as public sector unions, that prevail in monopolising the short-term gains – while the long term pains are more widely distributed and are especially unkind to the poor. This is a governance problem.

Fiscal Responsibility Act and Parliamentary oversight

The Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act No.3 of 2003 was meant to be a governance solution to this longstanding problem of irresponsible spending and debt creation by governments in election years. It requires the government to publish five types of reports, including a pre-election budgetary position report that should be published within three weeks of a parliamentary election being proclaimed.

However, the responsibility of adhering to the Fiscal Responsibility Act has not been adequately shouldered by either the bureaucracy or parliament of Sri Lanka. The Act is also unable to deal with problems created by fiscal liabilities being concealed within State Owned Enterprises, such as banks, covered by sovereign guarantees. Previous Verité Insights have also highlighted the existence of issues, such as a ‘slush fund’ within the budgetary disbursement mechanism.

The Open Budget scores the level of disclosure in budget documents. Sri Lanka ranked 69th out of a 102 countries on the 2015 Survey (evaluating 2013 performance). It found that the Government of Sri Lanka has failed to publish documents to the public in a timely manner, and it produced ‘minimal’ budget information. Oversight of the budgetary process during the planning and implementation stage was also identified as insufficient.

Budgets are not just economic documents, they are governance documents, that are supposed to outline revenue and expenditure plans and responsibilities over several years. They are expected to be the foundation and set the direction for the governance of the country. There is presently some hope of restoring the responsible management of budgets.

In December 2015, the parliament adopted 16 oversight committees and also a powerful committee on public finance. It has huge powers to enhance the visibility and accountability of budget creation and implementation in Sri Lanka. It is the type of governance solution that is solely needed – however, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating.