Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the most common measure of a country’s prosperity; it is an imperfect means of assessing wellbeing in an absolute sense, but the changes to GDP is a valuable indicator that the economy is progressing and of what is driving increases in employment and incomes.

At the end of 2013 Verité Research published an Insight titled: The post-war bump has hit the ceiling. The point was that Sri Lanka had been driving growth in boom and bust cycles. This was done by ballooning consumption imports and bringing pressure on the trade deficit, accelerating construction – especially in the bust cycles of import trade, and putting pressure on the fiscal deficit. The Insight argued that this was unsustainable.

The present Insight shows that the lesson has not been learnt. The post war growth story of Sri Lanka remains one of inflating consumption imports or construction. In short, the unsustainable strategy is being pushed to breaking point, and it is still unsustainable.

The trade deficit: boom, bust, and boom

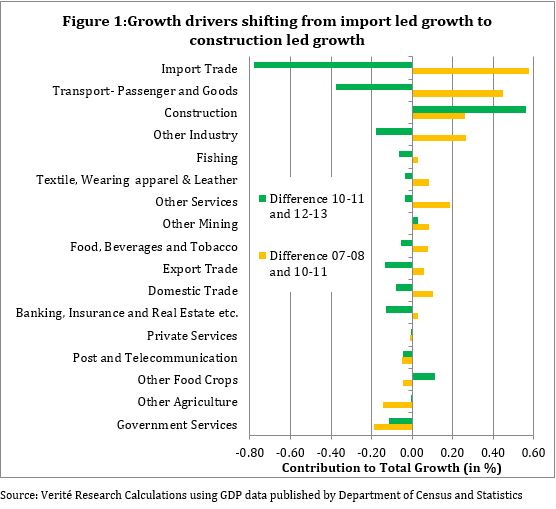

The war ended in 2009. Comparing the difference in the contribution each sector made to growth, in the two years before (2007-2008) and the two years after the war (2010-2011, see figure 1), the post-war bump comes mainly from import trade, then transport – which is connected to import trade. This is followed by an increase in the growth of construction as well as in industry. To understand the figure, when bars extend to the right, it means that these sectors became a driver of growth (growing more than the period compared against) and vice-versa.

The boom in import consumption was driven mainly by short term reductions in import taxes, post-war consumer confidence, and an exchange rate that was held unsustainably low by the Central Bank (this makes imported goods cheaper and locally produced goods relatively more expensive).

This was essentially a short term strategy. It caused the trade deficit to expand to over 15% of GDP, and caused the exchange rate to buckle under the pressure – which led to a damagingly sudden devaluation of the currency by over 10% in a space of a few months between the end of 2011 and the first quarter of 2012. The government was also forced into a series of policy reversals to help dampen import growth, adding uncertainty into the mix of instability in Sri Lanka’s economic environment.

As a result, the next two post-war years (2012-2013) had a very different sector profile of growth drivers compared to the first two years (2010-2011). Import trade went south, as did transport along with it. Further, even industry performed less well. All this can be seen in Figure 1.

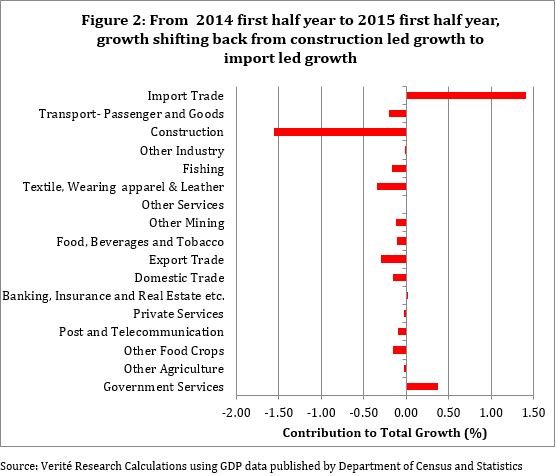

Instead of learning the lesson and working out how to stimulate growth in other sectors of the economy in 2014 and 2015, government policy makers once again took the lazy way out. Figure 2 shows the difference between sectoral contributions to growth in the first half of 2014 vs. the first half of 2015. Towards the latter part of 2014 and the first half of 2015 policies were reversed yet again to encourage imports, and another growth cycle based on expanding the trade deficit was squeezed out yet again – squeezing that strategy to its pulp.

And of course by the latter part of 2015 the currency faced another sudden depreciation of about 10%. Growth by ballooning the trade deficit reaches its limit very quickly. It is not sustainable in theory, and has proved so in practice as well – repeatedly. But attention to either theory or history has not been the strong point of Sri Lankan policy making in the post-war years so far.

Construction grows, booms and crowds-out

The significant growth in construction in the first two years post-war turned into a stampede of growth in the next two years as the import led growth went bust. By showing a massive expansion in spending on construction, the government was able to push up growth; with construction making up ground in the total GDP calculations, despite the fact that almost every other sector did worse.

The problem is that the construction growth is mainly financed from the government budget. With the government’s revenue share of GDP lagging, the consequences of increasing expenditure on construction goes three ways: first, it tends to increase the fiscal deficit; second, to finance the deficit, it increases debt; third, to reduce the debt and deficit, it crowds out spending on other important sectors such as health and education. Previous Verité Insights have shown evidence of all three of these consequences in the first five post-war years.

In 2015, with the government reprioritising its spending, paying for irresponsible election promises made since 2014, debt and the deficit facing inherited pressures, it has given up on the massive continued expansion of construction, which is unsustainable in any case. Even if construction had received the same expenditure as in 2013 and 2014, it would not have contributed any more to growth than 2014 (see Figure 2). Growth comes from continued expansion over the previous years.

Outlook for 2016

The unsustainability of the current path is becoming manifest. The government is already taking steps to curtail imports, especially vehicles (comprising 12% of all imports in the first six months of 2015), which was the main contributor to the surge in imports.

Almost all sectors other than import trade and government services performed poorly in the first half of 2015 compared to the same period in 2014. This is because increasing GDP growth in a sustainable manner requires serious administrative and policy reforms involving the public sector, in skill development, in the structure of economic investment, in production and exports, in regulation, through technology improvements and by solving the many bottlenecks to economic functioning in Sri Lanka.

Shortcuts are short-lived; and have been already squeezed out, perhaps to the limit, in the post-war years. Both the trade-deficit short-cut and the fiscal-deficit short-cut which previously had to be substituted in turn, have now run their course together. This leaves the government with facing up to the hard work of finding genuine means of increasing the production and productivity of the economy. Failure to do so will register itself in reduced GDP growth. Attempting to postpone the pain by rolling out more short-cuts will place the economy on an increasingly precarious path to future pain.