The annual budget is one of the bedrocks of successful government. Budget statements are not simply accounting statements, they are statements of planning and governance, where the government announces its intentions and sets expectations on outcomes. Budgets presented in the Sri Lankan parliament have a track record of setting expectations that are not honoured in practice. Large deviations between budgeted allocations and actual expenditure raise concerns about bad faith and deception in the budgeting process.

Previous Insights published by Verité Research in 2014 ‘Who bleeds for the Budget?’ and ‘Agriculture and defence budgets reveal unstated priorities in policy’, highlighted large gaps between what was promised in the budget and what was delivered between 2010 and 2014. The present Insight sets-outs an analysis of more recent budgeting on social services and the rural economy.

Overall, the Insight makes three observations: (1) Promises are better kept in election years: Budget commitments on social spending are more likely to be honoured in election years, and breached in others. This supports the concern of deception, as it suggests that failure to keep the promises on spending is likely to be wilful, rather than a problem of ensuring implementation; (2) Budgets make unrealistic promises: Budgets tend to make grand allocative promises without a realistic plan – suggesting an approach of planning to fail, or bad faith in terms of the announced commitments; (3) Public awareness/interest matters: Overall, promise-keeping on budgets is better on tangible direct transfers and handouts, which are likely to be noticed immediately by the public if breached.

Post 2015: Promises broken after elections

This Insight analyses budgeted and actual expenditure of the government on social services which comprise of five sectors: Education, Health, Housing, Welfare (e.g. pensions, Samurdhi benefits etc.) and Community Services (e.g. garbage collection, disaster management services). In addition, the Insight also draws attention to another key sector: Agriculture and Irrigation, which is critical to the rural economy and for long-term poverty alleviation.

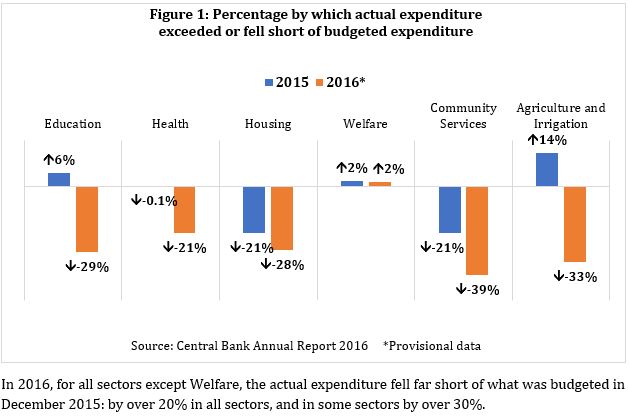

In 2016, for all sectors except Welfare, the actual expenditure fell far short of what was budgeted in December 2015: by over 20% in all sectors, and in some sectors by over 30%.

In contrast in 2015, where there were two elections in January and August, the results were different. In comparison to the budget presented in January 2015, there were three areas that saw increased commitment: Education, Welfare, and Agriculture & Irrigation, where the actual expenditure exceeded the budgeted amount.

Bad faith through unrealistic promises – planning to fail

In November 2015, the Verité Insight ‘Education and health in Budget 2016: Grand promises don’t bode well for governance’ warned that the budget commitments were unrealistic and the government was not proposing commitments that it could expect to honour. The actual expenditure data, now available, confirms the analysis in that Insight.

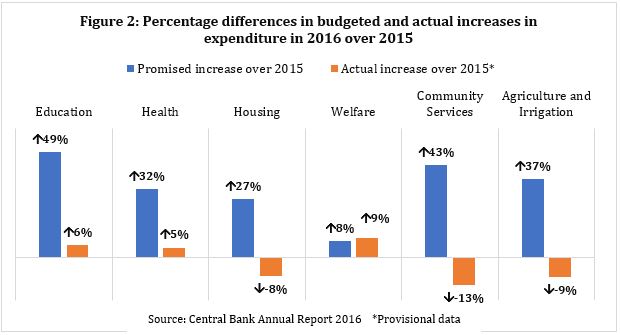

Figure 2 shows how much the government budget promised to increase nominal expenditure for each sector in 2016 over its actual expenditure in 2015 and contrasts it against the actual increase in 2016 over 2015.

This analysis further confirms the concern on grand promises. Apart from Welfare, the government promised increases of above 25% for Housing, over 30% for Health and Agriculture andIrrigation, and over 40% for Community Services and Education. The actual expenditures, however, failed to deliver. Increases in Health and Education were around 5% (approximately an inflation adjustment only). Expenditure on Housing, Community Services, and Agriculture & Irrigation actually declined between 8% and 13% in nominal terms.

Public awareness/interest matters

In the case of broken budget promises after the election year, Welfare expenditure was the only exception. In the case of unrealistic budget promises as well, Welfare expenditure was the only exception. The promised increase for Welfare in 2016 was not grand – it was to increase by about 8% (less than for any other of these social sectors) – and it was generously met with an actual increase of around 9% (more than for any other of these sectors).

It is noteworthy that tangible direct transfers account for 84% of the Welfare expenditure: pension payments (to retired government servants) are 68% and Samurdhi benefits (to poor households) are 16%. Large numbers of the population benefit from these transfers. Over 580,000 people receive a pension in Sri Lanka, and over 25% of Sri Lankan households receive the Samurdhi benefit.

The new Ministers of Finance

Successive governments have continued to highlight the significance of the Education, Health, and Agriculture and Irrigation sectors to the economy and these are stated priorities in the country’s development model. However, successive governments have been able to use the budget to mislead people on the actual (rather than rhetorical) priority being placed by the government on these three sectors. The lack of monitoring and public awareness on the delivery of budget commitments enables the Ministers of Finance to silently reverse the promises made in the budget, without being held accountable.

Mr. Mangala Samaraweera was assigned the cabinet portfolio of Finance and Media and Mr. Eran Wickramaratne was made the State Minister of Finance in May 2017, almost halfway into the government’s term. Such mid-term appointments usually come with new hope and expectations. These two Ministers now have an opportunity to break away from past practices, and present a budget that will be followed through in practice.

In September 2015, Sri Lanka’s new Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Samaraweera made a bold statement at the 30th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC). He said “Therefore, I say to the sceptics: don’t judge us by the broken promises, experiences and U-turns of the past…”.

However, two years down the road, Mr. Samaraweera’s statement has only added to Sri Lanka’s list of broken promises to the United Nations. Perhaps now, as Minister of Finance, Mr. Samaraweera can repeat his words at the next budget, and this time, have a better shot at seeing it through.

The budgetary planning process for 2018 is currently taking place and in a few months, the new Ministers will be presenting a new set of budget commitments for 2018 and beyond. Will the new Ministers of Finance ensure that the promises made are sensible and realistic (not plann to fail); and that there is sufficient planning and monitoring to keep the promises that are made? This is the 17 billion dollar question.